Don’t Judge a Woman by her Cover: the Hijab and Unethical Judgments

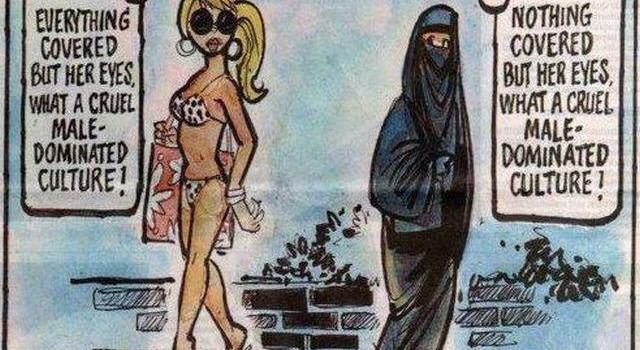

Please don’t judge hijabis for reasons pertaining to their hijab.

And I know this is a request that might make us all start with the ‘but theys…’. Let’s hold off on that for a minute.

Because I’ve done it too. I do still, sometimes, and catch myself. Even though I wore the damn thing myself for 15 years and knew what it was to be painted in whole swaths of ugly colors because of it.

It’s just so easy to other.

And no, it’s not a request reducible to ‘you never know; she might be forced into it.’ Yes, that’s some of it– you can’t tell by looking at hijabi if she’s a closeted atheist or a devout Muslim woman or somewhere in between. There are so many problems with saying “what’s on her head is a reflection of what’s in her head”, to say the least because the hijab as such doesn’t reflect one common belief or set of beliefs for all women who wear it.

But that’s not even close to being entirely it at all. It’s about much more than those who are physically forced to wear the hijab. And even that gets tricky, because physical coercion doesn’t preclude ideological conviction. Sure, a hijabi might be beaten or worse for showing some skin. That doesn’t mean she must have any individual desire to independent of that.

It’s about a lot more than conviction in any case.

It might seem like a paradoxical request–after all, the hijab is a publicly coded way a woman arrays herself, seemingly inspiring also-public commentary. It’s the way she is seen in public and only in public, for the eyes of others–a little different than women who fashion their own clothing styles for themselves, whether or not others see them. It’s a purposely and exclusively public mode of dress (even if particular stylistic choices in conjunction with it are not), perhaps even a statement for some, of belief or identity. You might know hijabi women who have liberal families who wouldn’t impose it upon them. You might know hijabi women who live in countries where they are free to dress as they please. Yes, I’m talking about them too.

I’m also talking about women in some floating in-between place, who wear the hijab but behave and interact in ways that seem to be at odds with the traditional understanding of it. Yes, I am talking about judging them as hypocrites too.

Let’s talk about the in-between cases, because they carry the burdens of both sides of judgment.

Tonight I learned a new term used to denigrate some women who wear hijab in Muslim communities in the West. The term, ‘hoe-jabis’ is used by some to describe girls who wear hijab in public but who will text and snapchat boys without their hijabs in private, or engage in other ‘immodest’ behavior.

And yes, this is offensive to hijabis.

But I also find it offensive to women. What problem is there if a woman who (I assume chooses to) wear hijab in the general public wants to privately show her hair and body to a boy she cares about? The two desires aren’t mutually exclusive for her actions to be hypocritical. After all, we as humans regulate our levels of intimacy and comfort in revealing parts of our hearts and bodies in many, many different ways, including barring the general public from what we reveal in private to those close to us. To suggest that a woman needs to line up her public and private performativity to suit the preferences of those looking at her is a fundamentally controlling and patriarchal viewpoint.

And snapchatting some boy doesn’t make her a ‘hoe’, which is a denigrating, slut-shaming slur you shouldn’t call any woman, regardless of intent (ie saying things like I don’t mean she’s an *actual* slut ffs does not actually absolve you). Dan Fincke over at Camels With Hammers perfectly expresses how and when intent is relevant when it comes to insults and slurs here. I thank him for taking care of that part of this argument so I don’t have to.

And if she wears hijab because others make her in some way, it’s even worse, because she’s basically being denigrated and attacked for trying to have some freedom within difficult and damning constraints, for trying to carve some sort of meaningful connection and expression within an already-limited life.

And let me stress strongly how incredibly unfair and ironic it is that hijabis are judged with harsher standards than everyone else for showing their hair. Non-hijabis aren’t attacked and called ‘hoes’ for walking around with their hair showing, but a hijabi is for snapchatting a boy her hijabless photo? And when hijabis have it all so much harder in terms of the scrutiny to begin with–and yes, they do, even the ones who choose it–that’s just the icing on the cake, isn’t it?

But, you might say, ‘I know these girls. I’m not judging them for their immodesty, I’m not slut-shaming them–I just don’t like hypocrisy, and it’s not like I’m judging them without knowing them. I know that girls X and Y come from liberal Muslim families that don’t make them wear hijab.’

If that is the case, perhaps you should ask yourself why they do it. And indeed you do, you say, well, why are they being fake? Why, why, do they do it, if they seem to care about modesty so little that they’ll snapchat boys in private? Why not just be immodest if that’s who they really are?

Did it not occur to you that they have reasons you are perhaps not privy to?

For one, people are not binaries who are/want only one thing all the time. Public modesty and private exhibitionism are not at odds. In fact, the first might make the latter even more wonderful and exciting. And that’s pretty okay.

But again, I ask, so what if their parents don’t make them?

Well, what does make them mean? Do you mean their parents don’t physically force them? Is physical force the only type of coercion? Is physical safety the only important consideration? If a person can choose to not wear hijab without being physically harmed, does that suddenly make it such that all requirements have been met for a choice to be considered not-coercive, free-enough?

Consider that parental pressure isn’t the only social force governing the quality and worth of a young woman’s life. Consider too that internal family dynamics are often not what they appear to be for the outsider, and you may not know as much as you think you do.

Consider that there are myriads of ways in which a young woman’s body is scrutinized and controlled by her family that are not expressible in an explicit desire that she cover her hair, but that covering her hair alleviates many of those pressures.

Consider that you may be assuming too much about the options the girls you know have to begin with. Consider that you may be making value judgments as to what they ought to consider important, what they ought to care about. Consider that a young woman in a Muslim community in the West might find herself better off trading in personal expression for social acceptance, and that she knows best what considerations she’s had to juggle to do that. Consider that there is a marriage crisis among American Muslim communities and stringent spouse competition, and women might choose hijabs because it helps them start a family. Consider that the difference between wearing hijab or not might be the difference between having friends, being loved, being less scrutinized, being more trusted and given more freedoms, being eligible for funding or educational opportunities.

Consider that the women in question are trading some freedoms in for access to rarer or more valuable ones, while trying to secretly salvage some of the freedoms they gave up. Would you blame them for trying to make the most of their circumstances?

Consider that wearing hijab might provide a woman suffering from a body image disorder with a socially-acceptable–even lauded–escape from scrutiny, and that by judging her for snapchatting some boy you might be denigrating her for being able to love and admire her body enough to share it with a few people who make her feel good enough about herself–that you might be denigrating her for becoming healthier, for being in less pain.

Consider that the woman you are shaming might be in transition from a hijabi life to a non-hijabi life, pulling her courage and conviction together bit by bit as humans must sometimes do, because we cannot erase the effects of a lifetime of enclosure on our bodies at the flick of a switch. Consider that by judging her in-between phase, you are making it harder for her to want to show her body to more and more people. Consider how ineffably difficult it is to begin to reveal your skin to other people when it has always been treated with shame and vicious scrutiny. Consider that the very things you blame the hijabi for doing might be tender, new, hesitant explorations at having a body that others can see, and see with kindness.

And oh, as an ex-hijabi, I can only say if only you knew how racking and painful it can be to try to reconnect with a body obscured for a lifetime.

Consider that the woman you are judging might be trying to come to terms with a choice that a younger version of herself made, that she may have felt differently about her hijab at one point in time, but that she made a near-socially-permanent decision branded in other people’s image of her, their treatment of her, and it is slow and difficult for her to build up the courage to break away from it under the massive scrutiny of a society that has already decided what she is and who she can be because of decisions she made in her past.

Consider that some people are ineffably shy, and shyness often manifests according to social norms, and covering might only be natural to a shy person in a Muslim community. Consider that you might be judging a shy, quiet person who is hesitant to let most people close to her body, but would balk at barring all from it, because she, like you, craves intimacy, craves love, craves essential human bonds.

There are ten million million possibilities that you cannot know.

No, even if you wear hijab or wore it, you cannot know. In my 15 years wearing the hijab, with all my intimacy and used-to-it-ness with it, I still encountered situations and environments I couldn’t imagine before they came upon me, that I reacted to in ways that would have surprised a former version of myself.

Consider that for many people, there are things more important than being able to bare your legs to the warmth of the sun and let your hair ripple in the wind, as amazing as those things can be.

Here you might say that, well, even if there are all these pressures, one doesn’t necessarily have to conform to them if they don’t have full conviction. Why cave? Why give in to the demands of society?

Because, dammit, people have to live. And living means a heck of a lot more than food and drink and physical safety. Continuity between ideology and action is a luxury in a misogynistic society.

And really, maybe they do have conviction. Perhaps consider that you are assuming that they don’t have conviction in their version of the hijab just because it doesn’t line up with the traditionally Islamic one, as if people don’t redefine and adjust social and religious norms to their own preferences, or agree with some values and not others, on a regular basis. Consider that the hijab she wears or doesn’t wear sometimes or all the time is *exactly* the practice she might have conviction in, and she’s not being a hypocrite at all. Consider that she might be wearing hijab for reasons other than modesty or averting the male gaze–I have friends who wear hijab for non-modesty reasons, and they are the same friends who are constantly hounded because their hijab is not-modest enough…despite there being no contradiction in having an immodest form of hijab if you’re not wearing it for the modesty.

Consider that even among those who do value modesty, it is quite possible for someone to have recurring but not constant desire for modest expression. Consider that by denigrating these women’s understanding of what they want their hijab to be as hypocritical, you are objecting to the evolution of social norms to more progressive alternatives.

And let me tell you, maybe you should ask yourself why you are so harsh upon those who you see as doing nothing but conforming to social pressure (as if that were an easy, burdenless thing!). Consider that when you denigrate the need for social acceptance, you are denigrating a need that you might not have because you may have never lacked it, or that you might be denigrating a need that is essentially human, that makes us happy and whole and well, connecting to others. Because isolation kills, and that is not a metaphor. Consider that when you denigrate the need for companionship, community, friendship, you are being superior and condescending about those who have less than you.

Even if you were once where they are, and hate who you were or what you did, even if you think you know what it is like to be there, and think that you yourself were a coward, a hypocrite, two-faced–do not project that upon others whose lives and circumstances are not yours, whose stories you don’t know. (And though this is your business alone, perhaps you might consider being kinder to your younger self).

Here you might say, well, can’t they conform in only the most necessary ways, instead of going to certain extremes? After all, even though plenty of non-hijabi Muslim girls are continuously hounded and harassed about the length of their sleeves and the scoop of their necklines, their hair is subject to less scrutiny, so why would they go as far as the hijab?

Well, consider that there are dual purposes for choosing something like the hijab. Hijabing up might immediately remove those harassments and pressures while at the same time filling a niche of acceptance within Muslim communities that is mercifully invisible in ways that a neither-here-nor-there dress code might not be. A woman wearing long pants and long sleeves with a hijab on her head is known to fit an established role, while a woman who dresses like a hijabi in every way but her hair is likely to stick out, to be subject to puzzlement, scrutiny, and even mockery. Societies have spaces that are well-worn, that are easier to groove into. People who fill those spaces tend to flourish in easier ways than those who straddle in-between, and that is worth a little extra hypocrisy. Again, because people have to live, dammit.

Consider that when you do use these labels as negative value judgments–fake, coward, hypocrite, weak–you are considering submission to power structures a matter of unique moral wrongness in one way or another, when the fact of the matter is that we all adjust our public personas to social norms and expectations all the time–that in various ways, whether we will it or not, we are all hypocrites, we are all pretending, at least a little. And for good reason. It is not practical, efficient, or safe to be all of ourselves to all people all the time. And though you might call this hypocrisy, it is not a shame.

Consider that those women might not want to be all the things you judge them as being–do you think they want to think of themselves as weak or fake or hypocrites? Do you think this is not a struggle for them, that your voice is not one they echo to themselves often? Consider that they choose, for instance, hypocrisy or submission over greater evils, to gain a less difficult life.

Consider that you are denigrating people for, whatever reason, making sacrifices that you don’t have to make, and then condemning them for trying to salvage a little bit of what they gave up in small ways, on their own terms.

Consider that you are participating in an ages-long patriarchal tradition of scrutinizing and labeling women for what they do with their bodies, when, how, and for what reason, and adding on to the labels and scrutiny of others: of the anti-Muslim bigots, the traditional, religious patriarchs slut-shaming even covered women, the hawk-like eyes of society in general.

Consider that when you stop judging her, you help her a bit. You help relieve some of the strain of constant judgment she inevitably suffers from.

It’s a little bit like fat-shaming. Fat people commonly encounter scrutiny and aggression and are even man-handled wherever they go from people who know jack-all about them and their bodily history. It does not help a fat person to be told they are unhealthy and need to lose weight, as if that is some startling revelation instead of being a constant, constant message reinforced at every turn all over media, social media, by friends and family and strangers. Your message is not unique. It is not a revelation. And you’re kidding yourself if you tell yourself it’s out of concern for that person. It is not original, insightful, or helpful. It is nosy, inappropriate, unkind, and often very cruel. Same goes for women wearing hijab in the West, same goes for women slut-shamed in a myriad of ways in the West.

And here’s the thing: it’s none of your business how women clothe their bodies, in public or in private. The publicity of a hijabi woman’s dress does not make it your business. She is not on the street for your perusal. She is on the street to live her damn life.

I understand that it can be very frustrating to see women engaging in dress codes you consider to be socially harmful, because you believe they bolster patriarchal norms of modesty, that they reinforce purity myths, because you lament the state of affairs that pressures women to conform to doctrines that reduce their values to their bodies or that treat an uncovered body as an object of social discord.

And I hear you.

But the enemy is not the woman who conforms to these imposed social norms, or who even chooses them in agreement with their values. Judging her for her dress not only does nothing to dismantle the purity myth or modesty doctrines–it only reinforces the values behind the patriarchal practice of scrutinizing and policing what women do with their bodies. You want to challenge the power structures that pressure and trap women, not blame women for caving under pressure, for making difficult choices. If you oppose the violation of a woman’s bodily autonomy, then you must oppose it regardless of the reasons that woman has for her bodily choices. There is far greater danger in policing bodies as a means of policing values than there is in preserving the freedoms that allow people to choose even regressive values for themselves.

And yes, I get frustrated too, to see women adhere to modesty doctrines, despite all of my empathy from my own 15 hijabi’d years. I have to fight my frustration sometimes when I see a hijabi on the street (speaking of hypocrisy! I am ashamed), but then I remind myself that I don’t know her story, don’t know her struggle, don’t know her reasons.

She could be me.

The point is that even though the frustration is understandable, it doesn’t justify judgment. It sure as *hell* doesn’t justify slut-shaming.

And you can’t imagine what it is like. It’s not like walking around wearing the hijab, even when you choose it, is easy. It’s not like women who wear the hijab don’t have difficult, challenging lives. Consider that when you judge a woman wearing hijab for being weak, or a follower, you are completely discounting the monumental struggle of it. Wearing the hijab is not borne of weakness. It is taxing far beyond all the judging, in ways that I haven’t the space to articulate, but that you can find here.

But the judgment is a plenty hefty cost on its own. It *isolates* you. It brands you. It turns your body into a beacon that everyone believes they have the right to judge because you arrayed it in a way that people think is a code for something they understand.

I wore the hijab myself for 15 years and every time I met a new person I admired, all I could do was hope and wish they weren’t judging me for the hijab on my head. Being closeted, it wasn’t exactly a thing that I could bring up to explain. I had to establish rapport, build trust with a few very close people before letting them know, know it all.

And damn is it difficult walking around with a supreme disconnect between what you are perceived to be and who you are. I feared the judgment of teachers I loved, professors I practically worshiped, department visitors whose talks I went to and had conversations with. People whose esteem and respect I wanted very much, who I didn’t want to be othered by because of an assumption that I held an entirely different worldview. It was one of the biggest struggles I had, trying to be close to people who shared my values while projecting the outward Muslim image and not being able to explain it away for fear of my own safety. And living in sectarian Lebanon, facing college classrooms full of judgy teenagers fueled with sectarian biases and knowing that I had ‘Shia woman’ branded all over me and they were evaluating me according to that information before I even started teaching them– that was almost as bad.

And with a lot of people I met and befriended, I didn’t realize how much anxiety I’d been holding in about the fear of judgment until I was in a position–often YEARS later–to explain it to them. I took a course with Dan Dennett when he was Visiting Prof at the American University of Beirut in 2011, and carried that fear around throughout the semester, although he showed not a smidgen of hostility or discrimination towards me for my hijab (in fact, he was immeasurably kind–one of the kindest professors I’ve ever had. He did me a great favor that semester that I shall always be grateful for–if you are reading, thank you, Dan). But understand, even when people are as welcoming and respectful as they can be, there is still a fraught existential discomfort attached to being compelled to present your body as not only other from what you are, but obscure it, present it in ways you hate–when you are, in the most essential ways, nothing more than your body. And it is constant, overbearing.

Not to mention heavy, heavy. I went on departmental trips, had dinner with Dennett and my other professors, attended an awesome conference on the metaphysics of evolutionary naturalism all without him knowing I wasn’t Muslim. I remember I used to deliberately be more vocal than usual about my agreement with concepts challenging religious values when they came up tangentially in our Philosophy of Biology course. I wanted him to know that I wasn’t a bigot–I wanted everyone to know that. I remember the *huge* anxiety that lifted from my chest when I began corresponding with him about being ex-Muslim and my blog stuff 2 years later. I still almost cry in relief when I get warm emails from him and other friends from that part of my life who finally know who I really am and who love me for it.

And this is important: It is anything but easy, anything but a frivolous choice to present yourself as other than what you are. The costs are weighty, long-lasting–I haven’t even begun to articulate half of the personal costs for me in this blog. I have so many half-written pieces trying to tease it out, but suffice to say that the lines can get fuzzy after years of splitting yourself between a public fictional self and a private true self. Consider that the women you judge might have good reasons for putting themselves through this.

And the isolation is toxic. The isolation of having judgment from both the religious and non-religious sides, of being accepted by neither, of being in-between, of it being extremely difficult to trust anyone and have friends, human connection, intimacy, love….that’s the worst. The worst.

And truly, far too many people are somewhere in that in-between–scrutinized both by the stringent religious powers around them and the critical non-Muslim observers.

So think again, next time you move to judge a hijabi on the street or in your social sphere.

There is so, so much to consider.

-Marwa

Why I have a donate button on my blog.

Why I have a donate button on my blog.

PS: My transition over to the Freethought Blogs is imminent! More soon.

PPS: Thanks to those who took part in our #TwitterTheocracy campaign yesterday. If you haven’t already, please sign our petition against Twitter blocking ‘blasphemous’ tweets from Pakistan. Use a fake address if you must, but SIGN ITTTT!!!!!

PPPS: This will have its own post soon, but I’m going to start an Ex-Hijabi Fashion Photo Blog soon! It will feature ex-hijabis with awesome hairstyles and tattoos and piercings. Ex-hijabis in bikinis and little black dresses. Ex-hijabis who are femme and ex-hijabis who are butch. Ex-hijabis topless and legsome and all decked out and minimalistic and with long hair and buzzcuts and everything. EVERYTHING. Basically ex-hijabis choosing how THEY want their bodies to look, finally. If you are an ex-hijabi with a desire to be featured, email me at [email protected]